The CIO Monthly Perspective

DISQUIETING EQUILIBRIA

Mounting pressure on the status quo

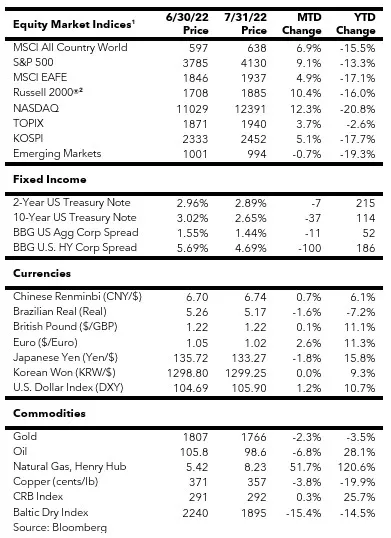

It has been a summer of extremes. Record high temperatures in the U.K. forced several airports to close temporarily due to melting runways. Fort Worth, Texas had an unusually high number of water main breaks due to ground shifts caused by extreme heat and a lack of rain. Eurozone inflation surged to record highs, prompting the European Central Bank (ECB) to surprise the market with a 0.50% rate hike that took the policy rate to a whopping zero. The Fed raised the Fed funds rate by another 0.75% but Chair Powell’s pivot away from forward guidance was interpreted by many investors as a dovish signal. With investor sentiment having turned extremely bearish by the middle of July, the dovish pivot narrative along with a better-than-feared earnings reporting season became rocket fuel for a sharp equity rally and a sizeable retreat in U.S. Treasury yields.

Despite the “bad-news-have-been-discounted” narrative and the seeming resurrection of FOMO (fear of missing out), fundamental risks have remained elevated. Putin continued to threaten the world economy by throttling the flow of commodities. A day after signing a deal to let Ukraine resume its grain exports via the Black Sea, Russia fired missiles at the port of Odessa. Europe is teetering on the edge of recession with its consumer confidence plunging to the lowest level on record. With Chinese consumer confidence also hitting record lows due to various social and economic issues, Beijing may seize Speaker Pelosi’s planned Taiwan visit to do something provocative in order to gin up nationalism. Two consecutive quarters of real GDP contraction in the U.S. triggered spirited debates over the definition of recession ahead of the midterm elections. Although the National Bureau of Economic Research is probably not ready to make a recession call, it’s worth noting that the prior ten occasions when the U.S. real GDP had two or more consecutive quarters of decline, all were labeled as recessions. The last time that back-to-back GDP contractions failed to make the recession roster was in 1947, which was affected by a sharp decline in post-war government spending.

The consensus 2022 earnings estimate for the S&P 500 Index has finally moved below the level at the start of the year, but 2023 is still projected to deliver high single-digit growth. There appears to be a replay of the earnings cyclicality from the Great Inflation era of the 1970s and early 1980s when elevated nominal growth – buoyed by high inflation – resulted in still positive earnings growth even after recession had started. However, earnings eventually succumbed to the weight of real GDP contractions and did not trough until several months after the recessions were over. If history is any guide, we have yet to see the lows for the current cycle and I continue to advise investors to stay patient, selective, and defensive.

FROM FOE TO FRIEND – AN UNEASY ALLIANCE

It had been a chaotic three weeks since Nobusuke Kishi reluctantly announced his resignation as Japan’s Prime Minister on June 23, 1960. The ensuing political maneuverings within the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) were finally settled when Hayato Ikeda was elected as the new leader and next Prime Minister at the party’s convention on July 14th. Kishi left the convention center in the early afternoon and headed back to his official residence to host a reception for Ikeda.

Reaching the pinnacle of power in Japan was a long and tortuous journey for the 63-year-old Kishi. His political life was thought to be over in August 1945, after the Allies arrested him as a suspected “Class A” war criminal. General MacArthur was pursuing an ambitious program to transform Japan socially, economically, and politically. The Japanese military was demobilized, and former senior government officials were being purged. Kishi was ranked high on the purge list as he was a minister in Prime Minister Tōjō’s war cabinet and had voted for and co-signed the declaration of war against the U.S. Prior to that, he was the mastermind behind the ruthless industrial policies in Imperial Japan’s de facto colonization of Manchuria that fueled the country’s war machine.

By 1947, MacArthur had to evolve his strategy in reaction to the Soviet occupation of Eastern Europe, Mao’s advances in the Chinese Civil War, and rising socialist and communist agitation in Japan. He soon reversed course and restored many former officials by allowing them to return to government bureaucracy. Kishi was released in 1948 without facing trial as he was regarded an asset by some Americans in helping to rebuild Japan.

Mao’s victory in 1949 and the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950 increased America’s urgency to create a stable Japan as a bulwark against communist expansion. The U.S. started to purge communists from the Japanese bureaucracy and accelerated the transfer of power to more conservative allies. The occupation of Japan came to an end with the signing of the Treaty of San Francisco in April 1952. However, as a precondition to restoring the country’s sovereignty, Japan had to sign a security treaty that allowed the U.S. to maintain military bases on Japanese soil indefinitely and to make use of them solely at the discretion of the U.S.

With the prohibition on former officials running for public office lifted in 1952, Kishi leveraged his wealth and ties with political and business elites to re-enter politics. He joined the Liberal Party and was elected to the Diet in 1953. Kishi was known as a master of “geisha house politics,” or behind-the-scenes maneuvering. After failing to depose Prime Minister Shigeru Yoshida, the leader of the Liberal Party, Kishi took his faction to the Democratic Party, which won the general election in February 1955 under the leadership of Ichirō Hatoyama. With Yoshida having stepped down as the leader of the Liberal Party, Kishi led negotiations that resulted in the merger of these two parties into the new Liberal Democratic Party.

The conservative LDP received strong backing from the U.S., which was concerned that communism and socialism were taking root among Japan’s intelligentsia, students, and trade unions in the 1950s. The main opposition party at the time – the Japan Socialist Party – favored closer ties with the Soviet Union and wanted to recognize the communist regimes in China and North Korea. Kishi became the Eisenhower Administration’s favorite candidate to succeed Prime Minister Ichirō Hatoyama, but he lost a close contest in December 1956 to rival Tanzan Ishibashi, one of the most anti-Washington and pro-Beijing LDP politicians. Kishi settled for the position of Minister of Foreign Affairs, and then, as luck would have it, became the prime minister two months later when Ishibashi resigned for health reasons.

One of Prime Minister Kishi’s main policy initiatives was to revise the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty that took effect in 1952. The treaty was reviled by most Japanese people as a national humiliation and the cause for many anti-government protests. Kishi also sought to make the new security treaty a catalyst for abolishing Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution, which was interpreted to prohibit Japan from maintaining its own military. The U.S. was reluctant to revise the treaty, but eventually budged upon realizing that it was better to negotiate with Kishi, arguably the most pro-American Japanese politician, than risk being forced to deal with a less friendly figure later.

After more than two years of negotiations, the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security was finally agreed on. The new treaty addressed nearly all of Japan’s grievances against the original treaty and put the U.S.-Japanese security alliance on more equal footing. While the U.S. was allowed to keep its troops and bases on Japanese soil, it would have to consult with Japan on how they were to be used. The U.S. was obligated to defend Japan if it was attacked by another country. The new deal also allowed either side to rescind the treaty after an initial 10-year term. Kishi viewed the treaty as a crowning achievement that would help extend his premiership. He triumphantly flew to Washington in January 1960 to sign the treaty with President Eisenhower, who accepted his invitation to visit Japan on June 16th to celebrate a new chapter in the bilateral relationship of the two countries.

To Kishi’s surprise, the new treaty turned out to be highly unpopular with the Japanese public and had unwittingly united leftist labor unionists, radical students, and right-wing nationalists to foment protests across the country. The opposition socialist party, in cahoots with Kishi’s rivals in the LDP, used a variety of tactics to stall the ratification process at the Diet. On May 19th, with Eisenhower’s planned visit being less than a month away, Kishi called for a snap vote on the treaty. When socialist members of the parliament staged a sit-down protest to block the vote, Kishi ordered 500 policemen to physically drag them out and then proceeded to ratify the treaty with only LDP members.

This “May 19 Incident” outraged the nation and led to the largest protests in Japan’s history. It culminated with radical students storming the Diet and clashing with police on June 15th, which resulted in the death of a female college student, Michiko Kanba. Desperate to stay in power long enough to host Eisenhower’s historic visit, Kishi floated the idea of mobilizing the Japan Self Defense Forces and yakuza gang members to secure the streets. However, with protests intensifying across Japan, Kishi had to inform Eisenhower, who had already started his nine-day tour of Asia, that the invitation to Japan had to be suspended indefinitely. It was also clear that Kishi’s resignation had become a prerequisite to restoring order in Japan.

Back at the reception at the prime minister’s residence, a relaxed Kishi was chatting with fellow LDP members when a balding, middle-aged man approached him. The unidentified man suddenly took out a knife and started stabbing Kishi repeatedly. The assailant was quickly subdued, but not before stabbing Kishi six times in the thigh resulting in profuse bleeding. The assailant was identified as an unemployed 65-year-old man affiliated with several right-wing groups. He never divulged the motive for the attack but claimed that he did not intend on killing the prime minister. Two years later, he was tried, found guilty, and sentenced to just three years in prison. Left unanswered were how he gained access to the reception at the prime minister’s residence, and how he came up with the substantial amount of bail while waiting for his trial.

Kishi survived the assassination attempt with 30 stitches to close his wounds. He stayed in the Diet until his retirement in 1979. He remained an influential figure in the LDP’s “geisha house politics” and continued to champion the cause of removing Article 9 and remilitarizing Japan until his death at age 90 in 1987. Nobusuke Kishi left a complex legacy but had a particularly strong influence on his grandson, Shinzo Abe, who took up his nationalistic causes and became the longest serving prime minister in Japanese history. Tragically, Abe was also a target of assassination but was unable to survive it like his maternal grandfather.

FATHER OF THE QUAD

It is too early to assess a politician’s legacy shortly after his or her passing or relinquishing power, as some decisions have impacts that won’t be felt for years. Former German Chancellor Angela Merkel was widely hailed as perhaps the greatest leader over the last two decades for her steadfast stewardship during various financial crises from 2008 through 2012; Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014; the influx of refugees in the middle of the 2010s; and, of course, Trump’s unpredictable presidency. The media loved to contrast Merkel’s measured responses to Trump’s ranting. For example, at a NATO summit in July 2018, Trump loudly complained on camera to NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg that “Germany is a captive of Russia” because the country will be getting between 60 to 70 percent of its energy from Russia with the new Nord Stream 2 pipeline. To the delight of the mainstream media, Merkel diplomatically repudiated Trump’s accusation by reminding people that she had lived under Soviet control in East Germany and was happy that a unified Germany enjoyed the freedom to make their own independent decisions. With the benefit of hindsight, we now know that the Donald was right, and that she lacked the so-called “vision thing.” Merkel’s place in history will be at the mercy of how Germany’s geopolitical and energy crises get resolved.

In contrast with the heaps of accolades bestowed on Merkel upon her retirement from politics, the late Prime Minister Shinzo Abe had never garnered much credit for what he had accomplished. Some have noted that the mainstream media punditry still refused to give Abe a fair shake even after his tragic death. CBS Mornings called Abe “a polarizing figure,” and a controversial “right-wing nationalist and conservative.” NPR called him “a divisive arch-conservative,” and “ultranationalist.”

I suspect future historians will likely rank Shinzo Abe as one of the greatest statesmen of the last decade for his strategic vision and alliance building. He was prescient in warning of the inevitable rise of China and its challenge to the rules-based world order, and he had great success in building a liberal democracy coalition as a counterbalance.

During his year-long first stint as Japan’s prime minister starting in September 2006, Abe introduced the vision of an “Arc of Freedom and Prosperity” aimed at forging a partnership among regional democracies with shared values, as well as common security and economic interests. Abe initiated the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, or the QUAD, among Australia, India, the U.S., and Japan in 2007. The security dialogue was carried out in conjunction with joint military exercises called Exercise Malabar. These moves prompted China to launch diplomatic protests against what it termed “Asian NATO.”

Abe’s strategic vision suffered a temporary setback after his resignation in September 2007. The QUAD was suspended in 2008 as Australia’s new prime minister, Kevin Rudd, abruptly seceded in order to placate China. The LDP’s landslide electoral defeat to the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) in 2009 ushered in a new prime minister, Yukio Hatoyama, who championed standing up to the U.S. and getting closer to China. The Stanford-educated Hatoyama was the grandson of the aforementioned Ichirō Hatoyama, a political ally of Abe’s maternal grandfather Nobuseke Kishi. In 2009, Hatoyama campaigned on revising Kishi’s 1960 U.S.-Japan Security Treaty and closing the U.S. military base on the island of Okinawa. His premiership wound up lasting less than nine months after failing to deliver on his promise of closing the base in Okinawa.

In late 2012, Shinzo Abe staged a political comeback with the campaign slogan “Take Back Japan” (Nippon wo torimodosu). Abe’s return to power coincided with Xi Jinping becoming China’s head of state, and the two leaders started to offer competing visions of regional security. In May 2014, Xi called for the creation of a new security cooperation architecture with China taking a leading role in crafting the code of conduct for the Asian security partnership. In an overt swipe at the U.S., Xi urged neighboring countries to completely abandon old security concepts and alliances based on outdated thinking from the Cold War and stressed that Asian problems should be solved by Asians. At the Shangri-La Dialogue in September that year, Abe emphasized that the rule of law should be the foundation for resolving security and territory issues to ensure peace and stability, and that Japan would become a “proactive contributor to peace” via the “reconstruction of the legal basis for security.” He was basically hinting that Japan’s Article 9 would be reinterpreted so that the country’s “Self-Defense Forces” could participate in overseas operations. A year later, the ruling LDP managed to pass a military legislation to make good on Abe’s words – a move endorsed by the U.S.

Over time, China’s militarization of the South China Sea, border disputes with neighbors, Xi’s signature wolf warrior diplomacy, and various illiberal policies convinced most regional players that Abe’s warnings were spot on. During the 2017 ASEAN Summits, the QUAD alliance was officially revived to counter China’s growing threat to the Indo-Pacific region. Today, the QUAD has become the cornerstone of America’s Indo-Pacific security and economic strategy. The U.S. has even rolled out the “QUAD Plus” concept by inviting other regional and Western countries to join the dialogue on various issues. Some suspect it might eventually morph into a NATO-like entity to counterbalance China’s regional ambitions.

Abe had also demonstrated tremendous political and diplomatic skills and perseverance in managing the tumultuous Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) saga. TPP, an Asia-Pacific trade agreement to the exclusion of China, was intended to be used as a counterweight by the U.S. against China’s rising economic clout. Abe had to overcome stiff domestic resistance from Japanese farmers and interest groups to get the country onboard with it. However, in January 2017, the newly inaugurated President Trump pulled the rug out from under them by withdrawing from the agreement. Abe stepped in to fill the leadership void and convinced the other ten TPP members on four continents to carry on. His efforts paid off with the signing of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), aka TPP-11, in March 2018. By early 2022, nine other countries, including the UK, were in various stages of application to the trade bloc.

Abe stepped down from premiership in September 2020 due to health issues but had remained an influential figure in Japanese politics and policymaking. Prior to his tragic assassination, he was the head of the largest faction in the LDP, a group originally founded by his grandfather Kishi. It is too early to assess the impact of Shinzo Abe’s tragic death on Japanese politics and the regional security architecture, but it could be a potential loss to the U.S. and an opportunity for China in the ever-shifting geopolitical dynamics. Over the last decade, the U.S. has taken for granted that Japan would remain a regional security stalwart thanks to Abe’s unflinching partnership. Going forward, without Abe’s prodding, Japan’s regional security commitment might turn more cautious, especially if Japan’s premiership once again becomes a revolving door – there have been 33 prime ministers since the current constitution went into effect in May 1947, implying an average tenure of just 2.3 years. A few days before Abe’s tragic death, former prime minister Yukio Hatoyama, speaking at the World Peace Forum hosted by China’s Tsinghua University, accused the current Japanese government of playing up ideological differences to help the U.S. encircle China. While Hatoyama’s pro-China view is not widely shared in Japan these days, potential economic issues may erode the electorate’s support for the LDP’s plan to double Japan’s defense spending to 2 percent of GDP over the next five years. Japan’s strong support of Taiwan, long championed by Abe, could also lose steam as so-called “panda huggers” in the LDP exert more influence on the more moderate Prime Minister Fumio Kishida. It remains to be seen who will pick up Abe’s mantle and fill the power vacuum in the LDP’s biggest faction. However, no contemporary Japanese politicians can match Abe in stature and influence.

FROM ABENOMICS TO A CRASHING YEN

Shinzo Abe is perhaps best known to global investors for Abenomics, his ambitious economic program to revitalize Japan’s economy with so-called “three arrows”: aggressive monetary easing, accommodative fiscal stimulus, and structural reform. The three arrows were aimed at tackling Japan’s 3D problems – deflation, debt, and demographics.

Abe entrusted Haruhiko Kuroda, the Governor of the Bank of Japan (BOJ), to prescribe the most aggressive monetary medicine to pull Japan out of deflation. On the fiscal side, Abe’s various fiscal stimuli were largely offset by two rounds of consumption tax hikes. On the reform front, Abe had achieved better corporate governance and greater labor participation among women. While overall results have been mixed, they are, perhaps, better than if nothing bold had been attempted.

Japan is the first advanced nation to experience population decline – its total population has dwindled from a peak of 128 million in 2010 to 125.7 million by 2021. More importantly, its working-age population (ages 15-64) has dropped 15% from a peak of 87 million in December 1994 to 74 million by May 2022. Japan’s shrinking population has exacerbated the deflationary pressure in its property market. According to the Bank of International Settlement, at the end of March 2022, the index of residential land prices in Japan’s six largest cities was 65% below the top of its real estate bubble in September 1990.

The bursting of Japan’s epic asset bubbles in the 1990s led to what economist Richard Koo called a “balance sheet recession” – many companies and households wound up with assets worth less than their debts. This negative equity issue led to a sharp contraction in consumption and expenditure despite extremely accommodative monetary policies designed to spur borrowing and spending. As a result, the government had to significantly increase deficit financed spending to avert a prolonged recession. Over time, Japan has evolved into the most indebted country in the world – its gross government debt exceeds 260% of GDP, and its net debt has reached 150% of GDP. Thanks to years of falling interest rates, sometimes in negative territory, debt servicing costs have remained under control. However, should the interest rate environment normalize too quickly, it would put a lot of pressure on the government’s finances.

After years of quantitative easing to suppress interest rates, the Bank of Japan now holds more than half of the government’s outstanding debt. Theoretically, the BOJ’s monetization of government debt should lead to higher inflation and a weaker yen, the desired outcomes, though in moderation, sought by Governor Kuroda. Lately, he has been getting what he has wished for, though not in moderation. With the Fed having accelerated its pace of tightening while the BOJ stubbornly kept rates near zero, the widening U.S.-Japan interest rate differentials have led to a 13% decline in the value of the yen against the greenback over the last five months. As the yen hit its multi-decade lows in the face of surging energy, commodity, and food prices, Japanese households are feeling the bite of inflation which has forced the government to offer more deficit-financed subsidies to ease the pain. In the meantime, traders are betting on further yen weakness unless the BOJ blinks and lets JGB yields move higher. Growing wagers on higher JGB yields have forced the BOJ to purchase a record $115 billion of bonds in June to defend its 25-bps yield cap. With just eight months left in his second term as the head of the BOJ, Kuroda is unlikely to loosen the grip on his controversial yield curve control policy. It will likely be up to his successor to normalize interest rates, which could unleash another bout of market volatility since the yen has been widely used for “carry trades” (i.e., borrowing cheaply in the yen to invest in higher yielding overseas assets). In short, the BOJ is trying to maintain an unstable equilibrium – artificially suppressing interest rates to rein in debt service costs while hoping inflation will rise by just enough to avert debt deflation. However, in the face of elevated commodity prices and policy divergence with other major central banks, the yen has become the pressure relief valve that transmits more inflation back home unless policy rates start to normalize. Governor Kuroda is probably praying really hard these days for an early Fed pivot to relieve the pressure on the yen.

DISQUIETING EQUILIBRIA

Japan is a cautionary harbinger for countries facing similar challenges with demographics, debt, and asset bubbles. Ironically, China, Japan’s main regional rival, has closely studied the risk of the Japanification of its economy but may find it hard to avert it. China faces a similar combination of a real estate bubble and a rapidly shrinking working-age population that has plagued Japan for three decades. China’s property bubble would have imploded if not for policymakers’ maneuvers to let air out gradually, just like Japan did three decades ago. The recently released UN Population Prospects report expects China to experience population decline starting as early as 2023. A shrinking population implies that China’s ambition of becoming the world’s largest economy by around 2030 will likely remain a dream.

Among OECD countries, South Korea, Germany, and Italy also face rapidly shrinking working-age populations. Italy is in the worst shape given its bloated public debt at 150% of GDP, which has made it the eurozone’s Achilles heel. As the ECB embarks on policy normalization, it is mindful that Italian bond yields could rise so much to effectuate another sovereign debt crisis. The ECB has introduced an “anti-fragmentation” tool called the Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI), which would allow for targeted purchase of public sector securities even during monetary tightening. The ECB is hoping that the mere threat of buying Italian bonds would help put a lid on the yield spread, but the market may move to test the central bank’s mettle at the most inopportune time.

Ironically, while the ECB was contorting its policies to bail out Italy, the country’s rightwing politicians reciprocated with more political chaos by forcing out Prime Minister Draghi, which may create an opening for Putin to break the EU’s solidarity with Ukraine. Putin realizes that, while most European political leaders have been siding with President Zelensky, the majority of Europe’s citizenry do not mind ceding Ukrainian territory to Russia for peace and cheap energy. With Boris Johnson and Mario Draghi, two staunch supporters of Ukraine being shown the door, political dominoes may start to fall in Putin’s favor.

KING DOLLAR REIGNS SUPREME, FOR NOW

The messy state of affairs around the world makes America look like a bulwark of stability and strength, and the U.S. Dollar Index has surged to two-decade highs in July as a result. Recently, investors have also taken a benign view on inflation, with inflation expectations having fallen back to pre-Ukrainian war levels. Markets have also gone against the Fed’s dot plot by pricing in rate cuts starting in the spring of 2023. All told, investors seem to believe that happy days (monetary easing and mild inflation) will soon be here again.

Behind the façade of Fortress America, there are serious long-term financial sustainability issues. According to the Congressional Budget Office’s July 2022 report, Uncle Sam’s net interest expense is projected to grow from the current 8% of federal revenues to 38% by 2052. By the late 2040s, our net interest expense could surpass all other budget items, e.g., social security and Medicare – to become the biggest federal “program.” These projections assume that interest rates will gradually return to a steady state of 3.8%, 2.3%, and 2.5% for the 10-year Treasury note, 3-month Treasury bill, and the Fed funds rate, respectively, by third quarter of 2027. Uncle Sam clearly has structural problems with spending and revenue collection, and something has to be done before it’s too late.

In light of America’s financial sustainability issues, it is unlikely that the U.S. dollar can maintain its current strength when the global economy finds its footing again. That said, foreign exchange is a relative game even if all fiat currencies are destined for debasement over time. As bad as Uncle Sam’s finances are, the U.S. is still one of the cleanest shirts in the dirty laundry bin. Over time, however, depending on the degree of mismanagement, the drop in currency value will show up in diminished purchasing power, aka inflation.

With the commodity complex under heavy selling pressure as of late – precious metals losing to the strong dollar and the market’s newfound optimism on inflation, and industrial metals and oil prices hurt by a fear of recession – investors should consider getting exposure to them in the context of a diversified portfolio. Gold’s 3.5% YTD decline is a disappointment given the inflationary backdrop. However, it remains a hedge on geopolitical crises and major policy errors, i.e., central banks blinking too early in the face of weakening demand and still elevated inflation. While the market has priced in benign inflation outcomes recently, I would caution that it had also assumed similar outcomes a year ago when the “inflation-is-transitory” narrative was in vogue. Industrial metal and oil prices could weaken further in a recession, but chronic underinvestment can potentially lift them higher when the eventual recovery gets underway. One can gain exposure to commodities via shares of well-managed mining stocks, preferably dividend payers to help soften the impact of volatility, and structured products tailored to provide some income and downside protection. In short, elevated uncertainty calls for diversification as well as some dry powder to capitalize on further market weakness in these uncertain times.